By APRIL LINDGREN, JAIGRIS HODSON & JON CORBETT

Local News Poverty in Canadian Communities

Presentation to the House of Commons Heritage Committee

Oct. 6, 2016*

April Lindgren, Ryerson University

Jaigris Hodson, Royal Roads University

Jon Corbett, University of British Columbia

*This is an updated version of the brief submitted to the House of Commons Heritage Committee on Oct. 6, 2016 as part of the committee’s study on Communities and Local Media.

Residents of Canada’s largest municipalities can obtain news from multiple sources, but it’s a different story elsewhere in the country. People who live in smaller cities and towns, suburban communities and rural areas have fewer options to begin with, and in recent years their choices have become even more limited. Traditional news outlets have been hit by cutbacks, consolidations and closures, while digital-first news sites often struggle to stay afloat.

Does any of this matter? The answer is “yes,” according to a report by the U.S.-based Knight Commission on the Information Needs of Communities in a Democracy. The commission’s report concluded that information is “as vital to the healthy functioning of communities as clean air, safe streets, good schools, and public health (Knight Commission, 2009, xiii).” It went on to argue that in addition to helping communities develop a sense of connectedness, access to information is essential in terms of holding public officials to account and making it possible for community members to work together to solve problems.

While local journalism is the subject of increasingly intensive scrutiny by scholars in the United States – Duke University’s Philip Napoli, for instance, is launching a project that will investigate the state of local news in 100 U.S. communities (Napoli, 2016) – there is much we don’t know about the Canadian situation and the extent to which the critical information needs of rural areas, towns and smaller cities in particular are being addressed. As Carleton University professor Dwayne Winseck warned committee members during his testimony earlier this year, there are “severe” shortages of information on changes to the media landscape overall. Moreover, he cautioned, there are “a lot of opinions and little data to act upon” (Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage 2016, 5).

Research on local news poverty

The gaps in knowledge about the state of local journalism in Canada prompted us to launch an investigation into what we call “local news poverty.” The purpose of this research, which got underway in summer 2015, is to:

- develop a crowd-sourced digital map to track changes to local news media/the supply of local news on a country-wide basis

- measure the extent to which some communities are better served than others in terms of access to local news

- determine whether social media and digital-only news sites are filling the gap when traditional print and broadcast outlets scale back or shut down

- investigate why some communities suffer from local news poverty while others have access to a relatively rich offering of local news

- examine what impact, if any, local news poverty has on civic/political engagement

- explore solutions to local news poverty where it exists

The news poverty project consists of two initiatives that are discussed below in more detail.

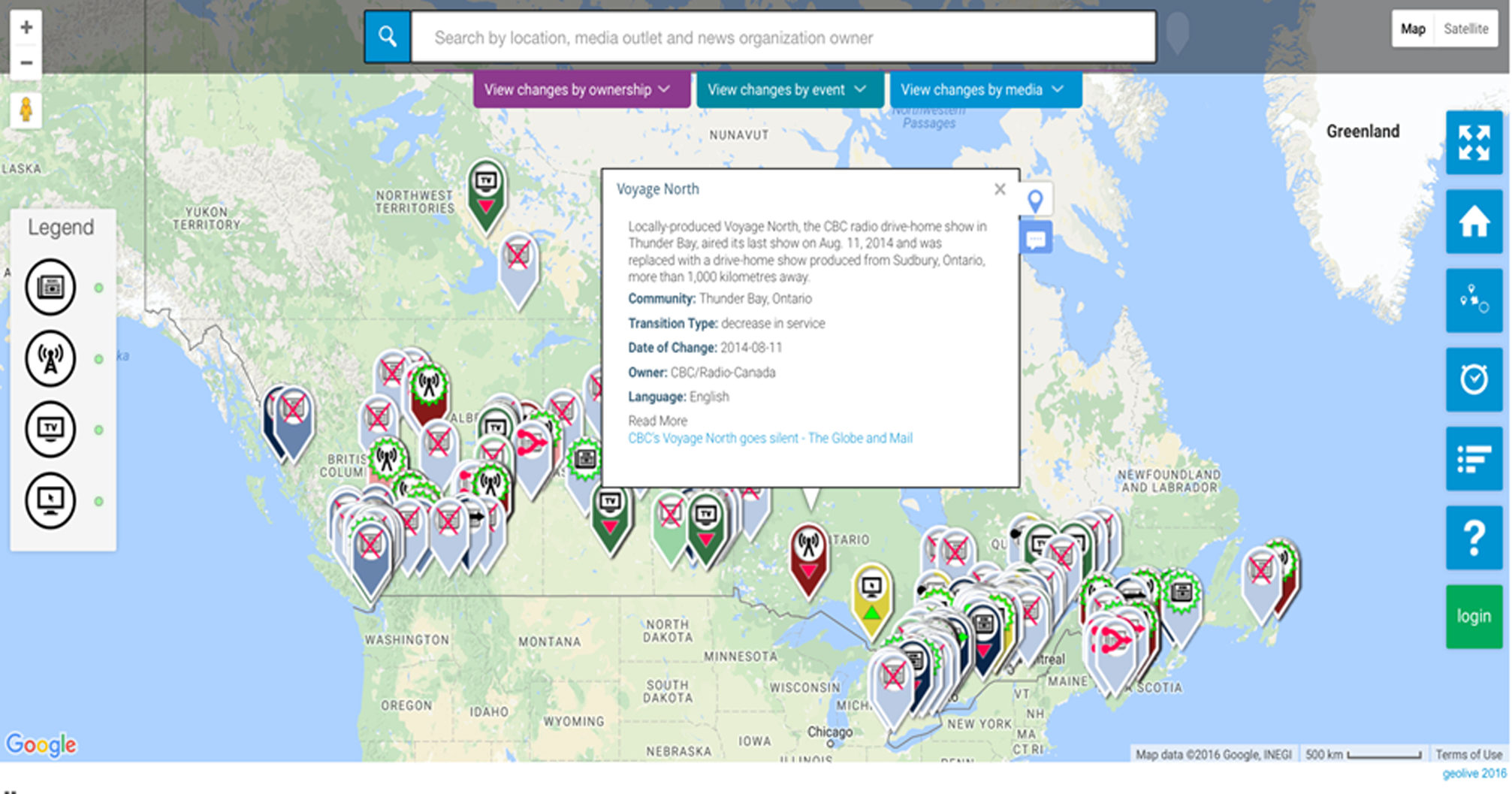

I. The Local News Map

The Local News Map is a crowd-sourced map that allows contributors to add information about changes – launches, closures, service increases and service reductions – affecting local broadcast, online and print media. For the purposes of this project, local news producers are defined as news organizations that demonstrate a commitment to accuracy/transparency and are devoted primarily to reporting and publishing original news about people, places, issues and events in a geographically defined community.

Figure 1. The Local News Map

https://localnewsmap.geolive.ca/

The map was launched June 14, 2016 on the journalism news website J-Source.ca (New research project…, 2016) and became the site’s most viewed item that month. It was created to spark debate about what’s happening to local journalism, generate data to inform that debate, track changes in local news availability, and help researchers identify patterns and trends in the local news sector. It is unique in that it allows users to get a big-picture idea of what is happening to local journalism and also to zoom in to examine what is going on at the community level. Users can also change the map’s filters to see what is happening a specific type of news media – community newspapers for instance – and to show the changes to local news outlets undertaken by different media proprietors.

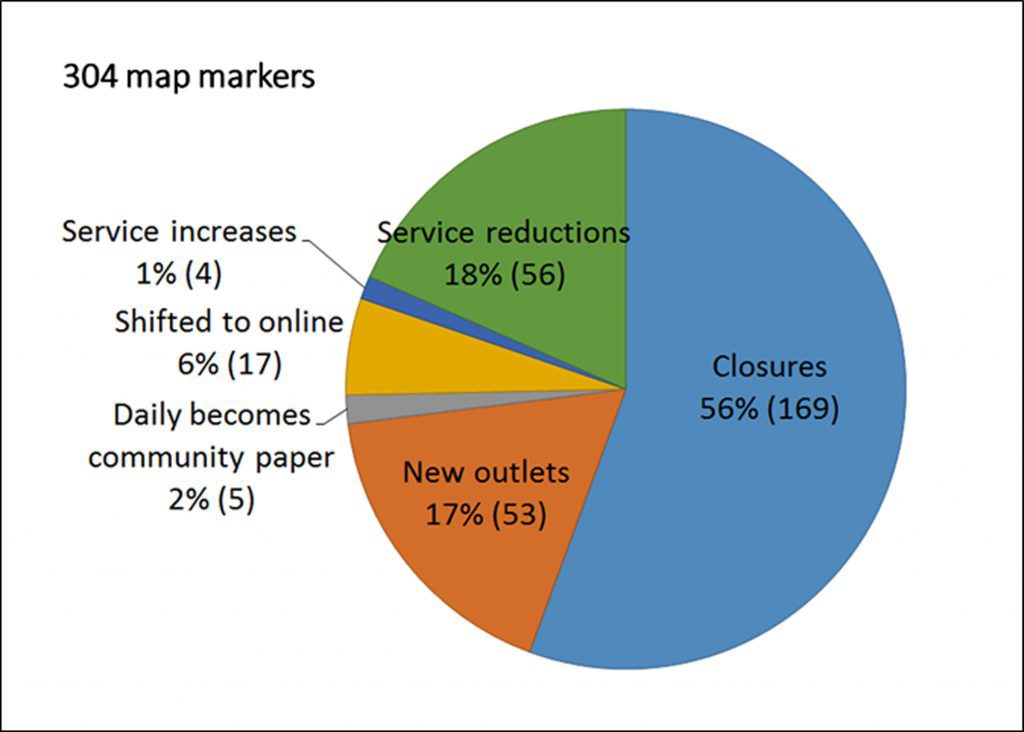

The map, admittedly, is only as good as the information that users add to it. We do, however, moderate the content for accuracy so we think the marker information is reliable and that the trends we are seeing reflect reality. What are we seeing? Four months after its launch, the map tells a powerful and disturbing visual story of newsroom closures that far exceed the number of new ventures. When we last examined the data on Nov. 7, 2016, there were 304 markers on the map highlighting changes to local news outlets dating back to 2008. Of those, 169 markers documented the closure of local news outlets in 131 communities. By comparison, only 53 markers highlighted the launch of new local news outlets.

Figure 2. The Local News Map: November 7, 2016 snapshot

*Closures includes closures due to mergers

**New outlets include new outlets due to mergers

II. Local news coverage of the 2015 federal election

The project’s second initiative is an examination of how local news outlets covered the contests for member of Parliament during the 2015 federal election. We focused on election coverage because the race to represent a community in the House of Commons is a major news event that warrants media attention. As such, while the quantity and quality of reporting on these races are worthy of study in their own right, they can also be viewed as something of a proxy for the overall performance of local news media in each community.

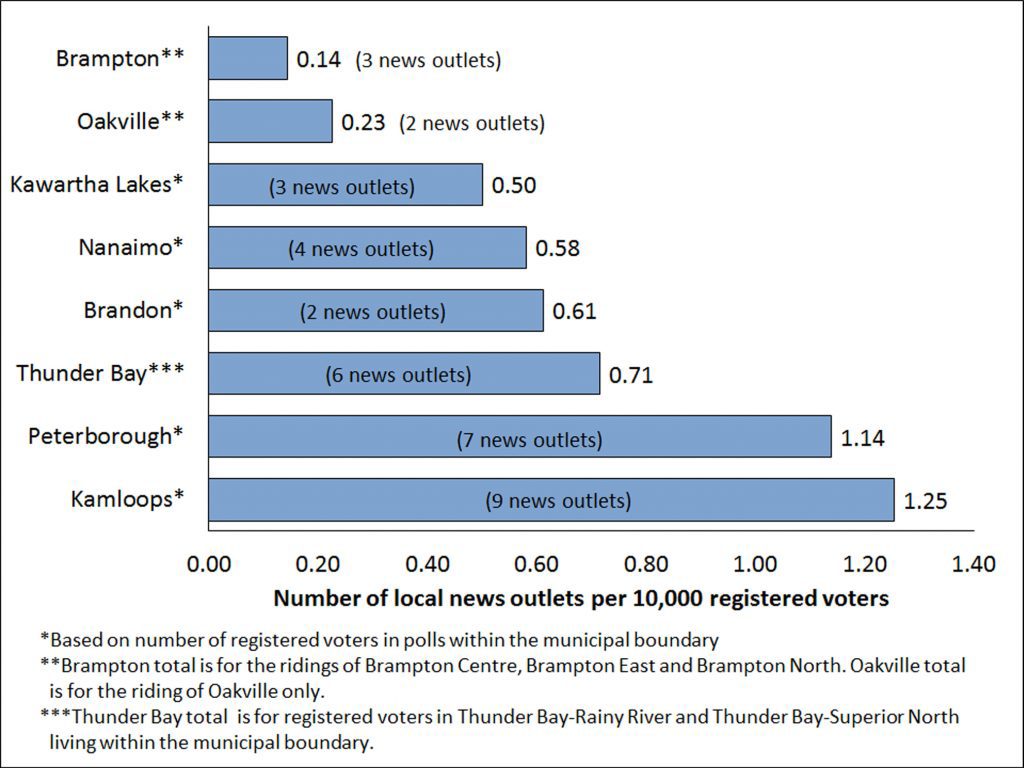

The study focused on news coverage by local media in ridings in eight Canadian communities: Peterborough, City of Kawartha Lakes, Oakville, Brampton and Thunder Bay in the province of Ontario; Brandon in Manitoba; and Nanaimo and Kamloops in British Columbia. After identifying the local news outlets available to electors in each community, we collected all of the election-related stories and Facebook posts they generated during the month leading up to the vote. We also gathered all tweets with the hashtag #Elxn42 and selected those that originated in our eight local communities for further analysis.

Coding of the stories involved separating national versus local stories; identifying the topic of each story; and then, for each local item, identifying sources who were quoted and whether the item was produced by the local newsroom or supplied by a wire service. The results to date point to:

- Significant differences in the number of local news sources in the different communities.

Figure 3. Number of local news outlets

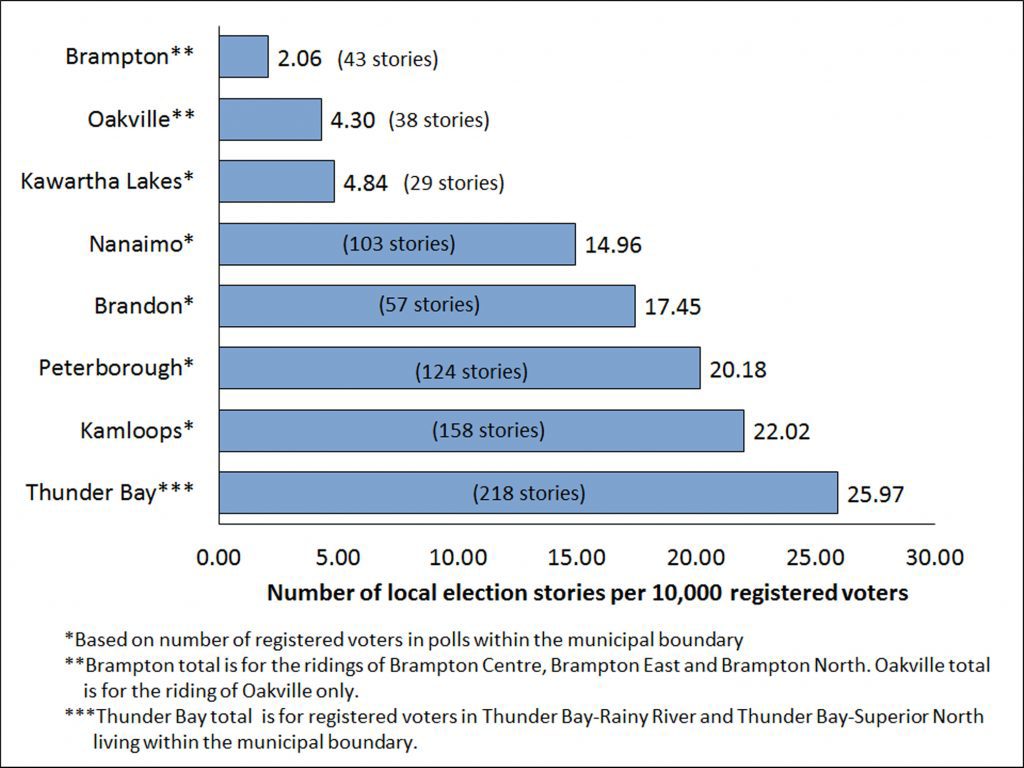

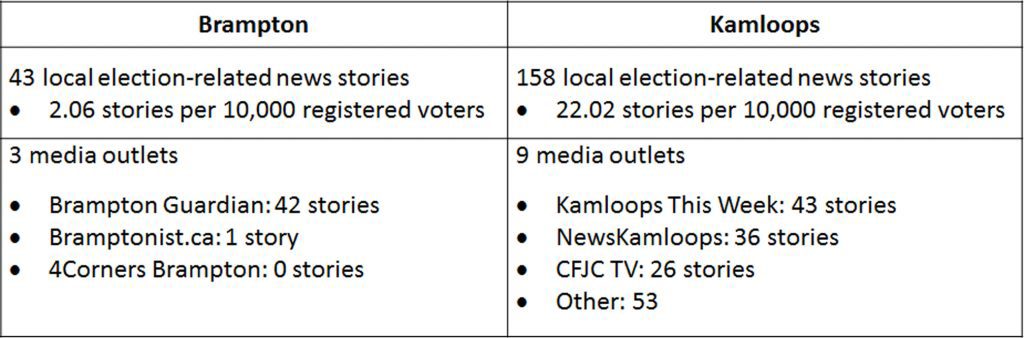

- Significant differences in the number of stories about the local race for member of Parliament. It’s worth noting that since the election, the local news landscape has deteriorated in two communities. The Nanaimo Daily News, which published 57 local election stories, ceased publication on Jan. 29, 2016. In Kamloops, Newskamloops.ca, which published 36 stories, ceased publication on Oct. 3, 2016.

Figure 4. Number of local election stories

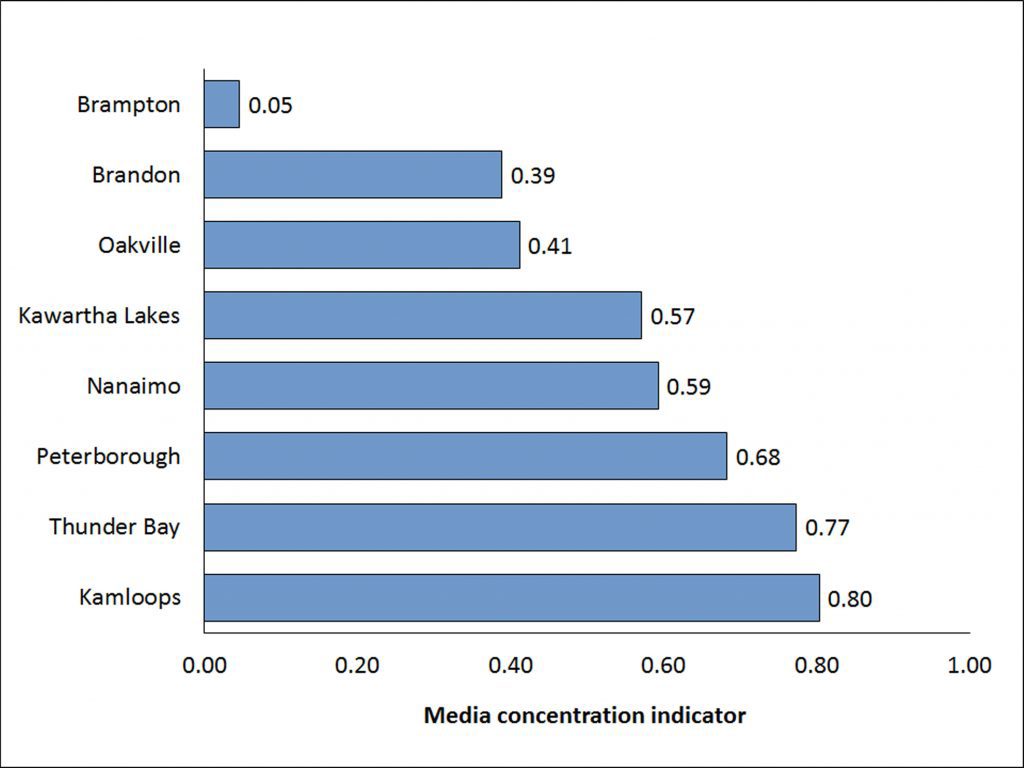

- A significant lack of diversity of news sources in some communities compared to others. The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (Brezina, Pekár, Čičková & Reiff, 2016), which we used to measure media concentration, shows that in Brampton just one local news producer dominated the provision of news about the local race for member of Parliament. In Thunder Bay and Kamloops, by comparison, the coverage was spread more evenly among local news outlets.

Figure 5. News diversity: media concentration indicator

*The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index measures the extent to which any news outlet dominates local news coverage.

A Tale of Two Cities

The data illustrate that the coverage of local contests for MP during the 2015 election varied significantly according to where voters lived. By all three measures registered voters in Kamloops, for instance, enjoyed relative “local news affluence” and coverage generated by a greater variety of sources than voters in the three Brampton ridings we examined (Brampton East, Brampton North and Brampton Centre).

Table 1. A Tale of Two Cities

Next steps

Creating a news poverty index

Why are some communities better served by local news organizations than others? Does it matter that residents of some places have only limited access to local news? If news poverty is an issue, then what should be done about it? This research aims to answer these and related questions, but to do that we need a way to distinguish between communities that are relatively “local news affluent” and those suffering from local news poverty.

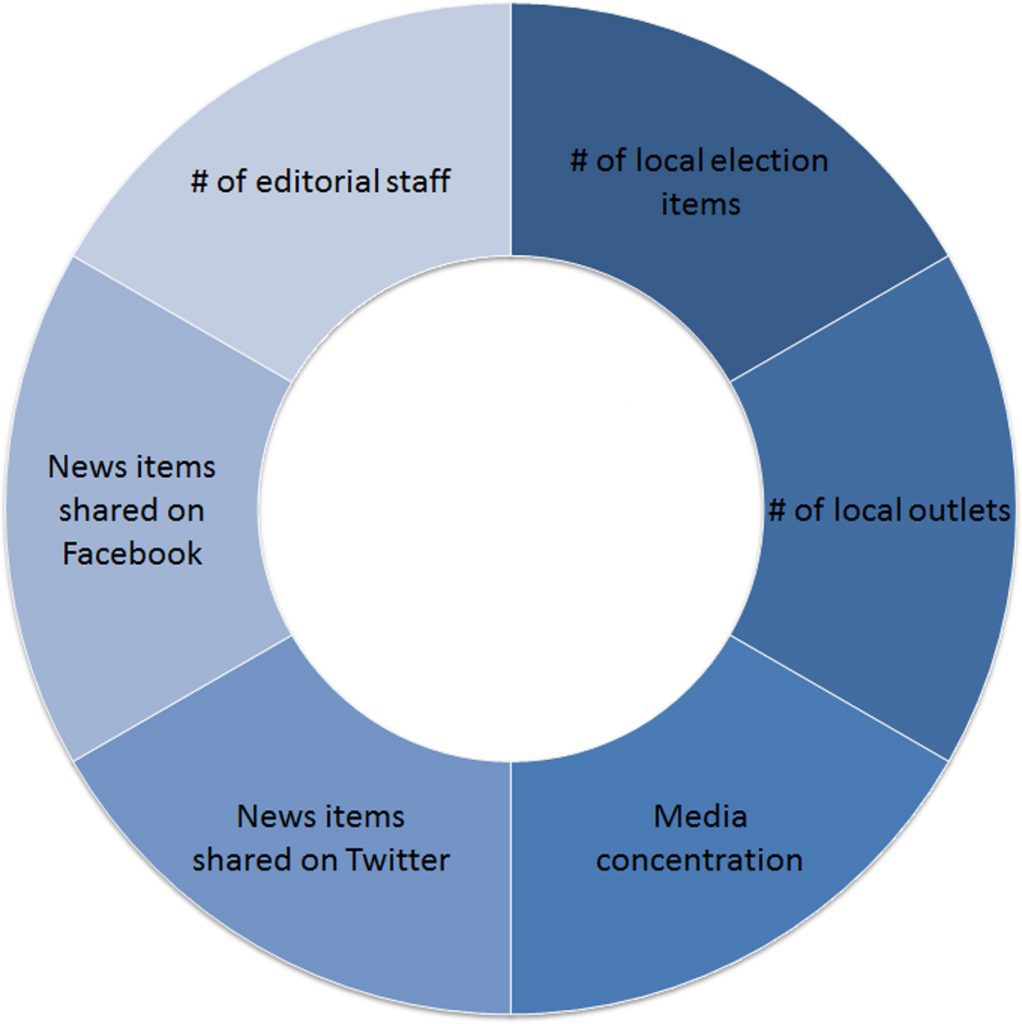

The next step in this research will be to devise a local news poverty index that we can use to rank the eight communities in the study sample. To create this index we could, for instance, combine and assign weights to the three news poverty indicators highlighted earlier in this report and also incorporate other variables (see Figure 6) to create a single number that can be used to rank the relative health of the local news landscapes in the eight communities.

Figure 6. The next step: Constructing a local news poverty index

The index will allow us to identify the communities where access to local news is most compromised, identify any potential contributing factors and over time, offer possible solutions.

In the longer term, our goal is to apply the lessons learned from our current research to a more comprehensive study of the availability of local news in general. Scholars have argued that access to reliable information is central to healthy economies and societies. Timely access to specific types of “critical information,” they suggest, is necessary for people to navigate everyday life, benefit from education and employment opportunities and, if they are so inclined, participate in local democracy (Friedland et al., 2012). To be more precise, the list of these “critical information needs” includes local information about emergencies and risks, health, education, transportation, economic opportunities, the environment and civic and political matters. In the Canadian context, if we can use The Local News Map and the local news poverty index to systematically identify communities where these critical information needs aren’t being met, we will then be in a better position to figure out what to do about it.

References

Brezina, I., Pekár, J., Čičková, Z., & Reiff, M. (2016). Herfindahl–Hirschman index level of concentration values modification and analysis of their change. Central European Journal of Operations Research, 24(1), 49-72. doi:10.1007/s10100-014-0350-y

Canada, Parliament, House of Commons. Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage. (2016). Evidence. 42nd Parl., 1st sess. 5, February 25. Retrieved From: http://www.parl.gc.ca/content/hoc/Committee/421/CHPC/Evidence/EV8128452/CHPCEV05-E.PDF

Friedland, L., Napoli, P., Ognyaova, K., Weil, C., & Wilson, E. (2012). Review of the Literature Regarding

the Critical Information Needs of the American Public. Retrieved From: https://transition.fcc.gov/bureaus/ocbo/Final_Literature_Review.pdf

J-source.ca (June 14, 2016). New research project examines local news poverty. Retrieved from: http://www.j-source.ca/article/new-research-project-examines-local-news-poverty

Knight Commission on the Information Needs of Communities in a Democracy. (2009). Informing Communities: Sustaining Democracy in the Digital Age. Washington: The Aspen Institute.

Napoli, P. (Sept. 26, 2016) Personal communication with April Lindgren.

The researchers:

April Lindgren is an associate professor at Ryerson University’s School of Journalism.

Jaigris Hodson is an assistant professor and program head at the School of Interdisciplinary Studies, Royal Roads University.

Jon Corbett is an associate professor in Community, Culture and Global Studies at the University of British Columbia Okanagan.

Acknowledgements:

The news poverty project has received support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the SSHRC-funded Canadian Geospatial and Open Data Research Partnership; the Canadian Media Guild/CWA Canada; Canadian Journalists for Free Expression; the federal Mitacs Accelerate Program; Unifor; and Ryerson University.

The project has benefited from the hard work and enthusiasm of research assistants Brock Campbell, Holly Clermont, Avneet Dhillon, Isabelle Docto, Eliana Macdonald, Brigitte Petersen and David Rudin. Our many thanks also to geoweb programmer Nick Blackwell at the University of British Columbia; Ryerson Journalism Research Centre coordinator Allison Ridgway and Christina Wong, data manager for the Local News Research Project.

Additional reading

Read more about the local news poverty research project: http://www.j-source.ca/article/new-research-project-examines-local-news-poverty

Visit the local news map: http://www.j-source.ca/article/crowd-sourced-map-tracks-what%E2%80%99s-happening-local-news-outlets-across-canada

Complete a survey about the state of local news in your Canadian community: https://localnews.typeform.com/to/fhXP4b